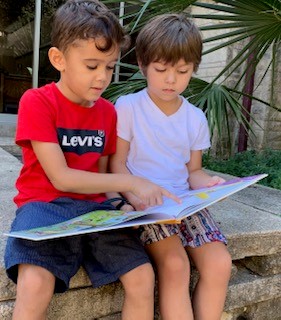

“Reading is not only fundamental to academic achievement, it’s also crucial to developing other measurable skills like executive function and social behavior. We are all agreed that reading makes you more knowledgeable and a better learner. What’s becoming more and more clear is that it also makes you a better-adjusted, better human being. Who wouldn’t prefer to see their kid immersed in a novel than scrolling dolefully through photos of a missed party on Instagram?”

A novelist recently told me that before having kids, she came up with a brilliant plan. Instead of punishing her child for misdeeds, she would instead order her to read a book. How better to turn a timeout into something productive and positive?

She excitedly informed an experienced parent about her plan who told her point blank: “That is the worst idea ever.”

This novelist now laughs at her naïveté. “Can you imagine if I had done that?” she said. “My child would have hated reading.”

So that much is clear. Do not punish your child by making him read, not even if he shoves his baby cousin unceremoniously off the swing. But there’s a more surprising corollary: Do not reward your child for reading either.

That’s right. You can say no to the back-to-school Read-a-Thon. No three cheers for finishing a book or dollar for every book read. No bonus iPad time if she would please finish one chapter of a single chapter book.

Just as reading shouldn’t be a punishment, it shouldn’t be rewarded. It shouldn’t be work and it shouldn’t be required to earn time for play. Reading isn’t something to plow through determinedly, accounting for each title.

All of this is why schools push reading so hard. That’s their job. But it’s not parents’ job. Schools may be the place where children learn to read; home can be the place where they get to read. For parents, the goal isn’t to push and/or to grade and/or to affix a gold star. It’s to help children realize that reading is the reward.

Most parents have absorbed the idea of extrinsic versus intrinsic motivation. Both get you to do things, but extrinsic motivation — external forces like financial rewards, academic honors and parental praise, or punishment and deprivation — are less powerful than intrinsic motivation, which is when you try hard because you want to. Intrinsic motivation is the real key to long-term personal fulfillment and success. Decades of research support this, whether the subjects under study are sugar-mad preschoolers or ambitious Ivy Leaguers. Moreover, extrinsic rewards can even feel commonplace in a culture that has thoroughly absorbed an “everybody wins” mentality.